This blog is not about lepidoptery. It is about another type of “butterfly” that every one of us has – the thyroid gland. More specifically, this is my blog about my life with Hashimoto thyroiditis, an autoimmune disease of the thyroid gland. If you too are affected, you might find some comfort in knowing you are not alone. I have suffered alone for many years and found that only those affected truly understand and empathise with your daily struggle. There were not many such people in my social circle and so I found myself increasingly isolated and socially withdrawn. Hashimoto’s changed me. When I became aware of this, I realised that I did not want to let it do that to me. I hope that blogging about my experience is a way to explore what I’m going through without feeling like I’m being a burden on my friends and family. And hopefully it will uncover some themes that are common to a lot of those who are affected by Hashimoto’s and provide some food for thought. Any comments are welcome.

This blog is not about lepidoptery. It is about another type of “butterfly” that every one of us has – the thyroid gland. More specifically, this is my blog about my life with Hashimoto thyroiditis, an autoimmune disease of the thyroid gland. If you too are affected, you might find some comfort in knowing you are not alone. I have suffered alone for many years and found that only those affected truly understand and empathise with your daily struggle. There were not many such people in my social circle and so I found myself increasingly isolated and socially withdrawn. Hashimoto’s changed me. When I became aware of this, I realised that I did not want to let it do that to me. I hope that blogging about my experience is a way to explore what I’m going through without feeling like I’m being a burden on my friends and family. And hopefully it will uncover some themes that are common to a lot of those who are affected by Hashimoto’s and provide some food for thought. Any comments are welcome.

My Little Butterfly and the “C”-Word

The “C” word – no, I’m not really censoring myself, although sometimes I do feel like swearing profusely. No, this “C”-word is more earth-shattering and profound. It’s the word that has been playing on a loop at the back of my head for the past months and that for a while I haven’t been able to say out loud, as if saying it gives it power over me. As if saying it out loud makes it more real. The “It” that shall not be named. It is my own Lord Voldermort.

Cancer.

It is a word that is charged with a lot of emotion, preconceptions, expectations and despair. It is a word that truly makes you realise that you lack one other C-word: control.

It’s not that I haven’t heard of this word before or thought about it. I raised money for cancer charities, I read articles, I know people who have had it. I just never really thought I’d get it myself. Didn’t realise how devastating the word really is to a patient. Until now.

I think I first knew or suspected I had it a few months back, when I discovered a hard small pea-sized something on my neck, just below the skin, where my little butterfly sits. I didn’t think too much of it, or didn’t want to think too much of it. A couple of weeks later I went to my endocrinologist, but I didn’t tell him about it, mainly because I did not want to be branded a hypochondriac again (different doctor, different country, but still…). He ordered an ultrasound of my thyroid, since in over 5 years of my Hashimoto diagnosis, I’ve never had my thyroid scanned (which this new endocrinologist in the new country thought was very unusual).

I went for the scan. It was a bit weird. Not uncomfortable. A glob of cold clear gel dumped on my throat. It smelled clinical. The transducer moved around the front and the sides of my neck area and I glimpsed at what the radiologist was seeing on the screen. I couldn’t make head or tails of it. And then the transducer moved to where the pea-sized hard thingy was sitting on my little butterfly. And it stayed there. And stayed there. And moved all around it. And pressed on it (and that hurt!). And circled it once more. I glanced at the monitor screen again (not an easy feat, as I had to roll my eyes all the way to the furthest top right my eyes would roll). The radiologist clicked a button and the screen lit up in red and blue. I still didn’t know what that meant, but the continued focus on the pea-sized hard thingy meant to me that it wasn’t anything particularly good. I think this is probably when my conscience quietly whispered the “C”-word to me for the first time.

I tried to put it out of my mind, at least until I got my results. A week later I was back again in my endocrinologist’s office, along with one of his students (it’s a teaching hospital). He told me that my thyroid was of a normal size (so no goiter, which I was almost certain I had, as the lower part of my throat seems to be protruding slightly and I sometimes feel it pressing on my trachea). He also told me that I had two nodules on my thyroid, one of which was 16mm in diameter and showed signs of calcification. That’s when I asked him if this is where it was found, pointing at the pea-sized hard thingy on my little butterfly, because, I said, I could feel it. He was a bit surprised by this, but wanted to have a feel as well, and directed his student also to do so. When I was asked to swallow whilst the physician’s fingers were pressing on the pea-sized hard thingy, I broke down in a fit of cough.

As a precaution, all nodules with over 1cm diameter in someone with Hashimoto’s get biopsied. Also, all nodules showing signs of calcification get biopsied. Doubly whammy. I got referred for a fine needle aspiration biopsy.

This was truly one of the most harrowing experiences in my life. I so so wished they had put me under! But no, no anesthetic. Instead, having been told not to move or speak, I had to feel the needle go all the way into my throat and then, once positioned, moved around a bit to get a tissue sample suctioned through the needle. It was painful – I can’t lie about this one. I’m lucky that I’m not too afraid of needles, but after this experience, my next blood test felt a lot worse than it usually does. To make matters worse, I had this needle inserted and moved around in my neck not once, but twice. I cried, I wasn’t even too ashamed of it.

What came next was even more anxiety-inducing: I couldn’t get my results. I was first told they would be available in 7 to 10 days. I called the hospital: they weren’t yet ready. I called the hospital again: still no. I then went on holiday, resolving not to think about it until I was back.

Once I was back in my endocrinologist’s office (minus the student), he seemed a bit… shifty. Too much small talk. Too little eye contact. He asked me how the biopsy went. I admitted it was one of the worst medical experiences in my life.

And then he said: “Unfortunately, the results are….. ” (pause).

Me, uncomfortable with the pause and thinking he might tell me that I would have to do it again as the sample collected wasn’t good enough: “Inconclusive?”.

“No. It’s really not good. Not good at all. I’m sorry.”

Me: silence. Shocked. Tear beginning to slide out of the corner of my left eye (why is it always the left eye?).

He proceeded to explain that apparently the second ultrasound (which was done in order to guide the fine needle biopsy) showed that my thyroid was in a much worse state than the first ultrasound let on. Apparently it had been completely riddled with Hashimoto’s. According to the pathologist’s report, the hard pea-sized thingy was, apparently, 95-100% malignant. There’s a 5% chance it’s a false positive and I was referred for a second biopsy to rule it our (or to confirm the first diagnosis). If the diagnosis is confirmed, I will have to have surgery. Recommendation: full thyroidectomy.

The “C”-word has taken on a new meaning in my life.

My Little Butterfly and the New Normal

I often find it very hard to answer one simple question: “How are you?”. It’s not because I’m hard of hearing or do not grasp the meaning of those three words. It’s just that there is no easy way to answer that question, at least not for me. Convention dictates that one answers this with “I’m well, thank you” and reciprocates by asking the same question. And this type of convention works in most settings: at work, at social events, polite exchange with your neighbour etc. This is not the type of conventional question that throws me off – in these types of situations it is not expected that one be honest about one’s well-being; it is simply an exchange of pleasantries, a way to minimise awkwardness around people one does not know very well or a polite bridge on the way to getting on to the more salient issue, such as “Oh that’s great, so do you have some capacity to do some work for me today?” etc. What throws me off is being asked this question by a relative, a close friend, someone who genuinely cares about me and wishes me well.

The reason I find this question so difficult to answer is that most days the conventional response couldn’t be further from the truth: “I’m not really well, thank you. In fact, I feel positively dreadful. I’m so tired even answering this question and being nice to you exhaust me. I would rather be in my bed than face today. And how are you?” seems hardly like an appropriate response and not one that anyone would wish to receive. Even when the people who genuinely care about you ask you that question. So you slap on your most winning smile and stick to the convention. Because no matter how much you try, you cannot adequately explain what effect Hashimoto’s thyroiditis has on your well-being, on your life. Because answers like: “Today I feel better than yesterday, but not as well as someone my age should feel” may appear like a positive response to you, but would be at best baffling to others; at worst, they may think you are not quite what they would describe as “normal”. And that is probably the truth. When you have Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and you are symptomatic, you may look normal to others, but you do not feel normal. Normal takes on a new dimension: it is relative to your worst-ever point in your illness or to how you remember you used to feel like before the onset of the disease. How you are on any given day may range between those two points, such that on some days you feel like you’re on top of the world and you forget you have this disease. On other days you feel so bad you hardly find the will to carry on. Anything in-between becomes “good”, or “normal”.

It has become my new normal.

My Little Butterfly and My Double Life

I am a happy person. I am an optimistic person – I’m the “glass is always full” kind of girl. Yes, that’s right, not just HALF full, it’s FULL full (one half is water, the other half air!). I am driven, energetic, curious, adventurous, smart, quick-witted, ambitious, passionate and a little bit wild. I am the one with the crazy ideas that people for some strange reason decide to follow through with. I am a vivacious storyteller. I am the one who laughs her head off without restraint. I am the life of the freakin’ party.

It’s just that sometimes I feel like this person that I know I am is not there. That person that I know I am has gradually been replaced by another. And it all happened without me noticing it as it happened.

At some point I woke up and realised I was no longer that person that I knew I used to be. Instead, I felt like I was lethargic, angry, pessimistic, I felt like I no longer cared (is the glass half-full or half-empty? who cares, I can’t change the way it is anyway…). I was too damn tired all the time. I slept for 10 to 15 hours a day when I could, but never felt refreshed. I put on a lot of weight and felt helpless about it. I exercised, though most of the time I felt too tired to do it. I ate well, though quite often I would slip up and comfort eat and not care. My sharp mind had become overcast in this thick fog (“brain fog” I called it, even before I knew that this is what it was called). I felt like I was always forgetting something (which I was!), and I became unsure of myself. I lost confidence, started having negative thoughts. I pushed people away. At first I felt too tired to go out and when I did go out, I realised I was not having any fun. I became disinterested in social chit chat. People who met met in that period referred to me as “aloof” (which was a very surprising thing to have said about the person who I know I was until then!). I became irritable and impatient. I was no fun. But as I started realising all this, I began to think myself worthless. I began comparing myself to the person I used to know myself to be and thinking to myself “how can anyone love the person that I have become?”. I began choosing loneliness over company, self-pity over conversations. I did not wish to “inflict” myself on others. I became withdrawn. I barely laughed anymore.

Mind you, this change was gradual. The two persona would be present at different times, the second gradually overshadowing the first. The person who I used to know I was would hide more and more often, letting the person I was becoming take the front stage. My friends and family did not notice for a while or they were too polite to say anything. I simply over time started receiving less invitations and honouring even fewer. I began breaking my commitments. I was too tired to even feel bad about it.

The person who did notice and was not too polite to say anything was one of my tutors. I will be grateful to her for the rest of my life. She had only known me for a few months by that point, but she knew that something was really really off with me when I started to underperform. I was no longer chatty in the classroom. I was forgetful, I would miss deadlines. By that point, however, I had been like that for at least a few years, I was just good at hiding it. I developed coping strategies. For example, I would revise for class on the day, so that the material was fresh in my mind, and would volunteer to answer the first question or start the discussion. This way I would be left alone for the rest of the class, the tutors satisfied that I had done my work. Except that I hadn’t (I only did about one third, which I so strategically volunteered, as I was simply too tired to do the rest. If I tried doing more the night before class, I would no longer remember the material when I woke up. I would stare at my highlighted and annotated pages and not recognise a single word.) But apparently I wasn’t fooling everyone. This tutor knew that something was amiss. Even though she never shared the details, she told me that she also went through something medical and had to make big changes in her life. She quit her high-stress job and became a tutor with more predictable working hours. Maybe this is why she saw the writing on the wall. At any rate, she approached me and broached the subject, advised me to take time off to figure things out. So I did. (In all fairness, a few more people noticed by then and talked to me, discretely. One of them was my yoga teacher who also hadn’t known me for very long by then, but for long enough to realise that on some days I was so weak and tired that I couldn’t even hold downward dog for longer than a few seconds).

I went back to my doctor, cried in his office and begged him to do every single blood test available – there had to be an answer to why I was feeling this way. Two years prior another doctor had already run a thyroid panel and my results showed a slightly underactive thyroid. Yet because my results were strictly speaking within the normal range, I was told to go away and eat more iodine-rich salt. I had gone back several times and was tested for diabetes and a range of other things, all testing negative. Doctors would dismiss me as a hypochondriac. By that point, nobody had bothered to check my antibodies. Nobody wondered about my high lymphocyte count. This time, as I sat in my (new) doctor’s office sobbing and using up a box of tissues, he agreed to run the full panel. I watched him tick all the boxes on the form and he himself drew several vials of my blood. A few days later I was asked to come in to discuss my results.

I was finally given a diagnosis. I was relieved. Finally I had two words to justify how I felt and why I had become this other person! My thyroid hormone levels were still only “subclinical”, but given the presence of thyroid antibodies, the doctor agreed to trial me on a low dosage of levothyroxine – 12,5 mcg leading up to 25 mcg over a couple of weeks. At first I felt worse. My body ached all over. Migraines were killing me. I would turn up to class and sit through it in sunglasses as my photophobia was so severe. I was asked whether I wanted to postpone my course. Grudgingly I agreed as at that point I felt I had no choice. And I’m glad I did. I was on bed rest for a week because my joint ache had become so bad I was barely able to move. I was sleeping on the floor as my back was too stiff and too painful to lie in (and get into) a bed. Apart from a few flashbacks of my “floorbed” (consisting of a memory foam bed topper dressed in bedlinen), the pain, pain medication and crying, I have no real memories of that time. I ordered a lot of books on Amazon. A lot of books about Hashimoto thyroiditis. I wanted to know what I could do about it, how I could reclaim my life, how I could again become the person that I used to know I used to be.

A couple of weeks later the fog lifted, the pain went away and I began to look at the light in the end of the tunnel. I began to crawl, walk, then run towards it. It was liberating! I was once again smiling, joking, making plans to see friends. I remembered what it was like to be the person I knew I was.

My excess weight melted off fairly rapidly. Perhaps it wasn’t just the medication but also me finally having some more energy and making better use of my yoga classes (spending more than half of it in child pose does not burn calories!). At any rate, I became leaner, keener and happier. I became me, again!

So far so good. But the symptoms returned a few months later. Again, like a silent ninja, they crept back, gradually, in disguise. Again it took me a while to realise that the person I knew I was had taken a few steps back, letting that other person come forward. I went back to the doctor and had my thyroid levels re-tested. My dosage was adjusted. I felt better. Then a few months later again, the same thing.

With my Hashimoto thyroiditis it is a continuous cycle. My dosage gets adjusted every few months. Sometimes too much and I go into hyperthyroidism, so have to go back, lower the dosage, get myself retested. I experience flare-ups, lately more commonly than before. It’s a wild rollercoaster ride. But through it all, I still remember the person that I know I am. Even when that person disappears for a while. I try to always remember that that person is the person I want to be. But I have also grown not to hate the other person, but to try and accept her. It is not her fault – she is my Hashimoto alter ego. She is a part of me and that’s how it will always be. This is how my little butterfly makes me lead a double life.

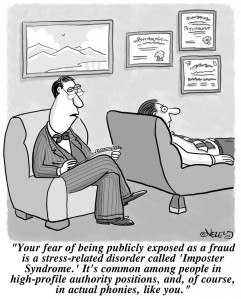

The hardest part of it is meeting expectations – the expectations of others and also my own. When I am the person that I know I am, I am still fearful that my Hashimoto alter ego will show herself at the most inopportune moment, especially in my professional life. When I am my Hashimoto alter ego, I pretend to be the person that I know I am, because this is the person that people expect me to be. It is exhausting. I sometimes feel like an imposter in my own body. How crazy is that, my little butterfly?

Living is more than existing

To live is more than to be alive, to exist.

Waking up in the morning, going through the motions and going to sleep at the end of the day, forgetting the things not done, the people not seen, the opportunities not taken is not living. Living is actually doing all these things rather than wishing you had.

To live means to feel, to want, to do, to hope, to dream, to savour. Just being is existing, but not living.

Living with Hashimoto’s often feels like not living. It feels like simply existing.

Existing and sometimes feeling only pain, both physical and emotional. Existing and feeling like you cannot speak up, like you cannot complain, since you’ve said it all before and people around you have not understood – why bother? Existing and keeping your thoughts and feelings to yourself. Do thoughts and feelings exist, or matter, if they are not expressed?

Existing and wishing and hoping for a cure, knowing full well that it will probably not come, but wishing and hoping that something could be done to ease the pain, to let you live again.

And at times, when this wishing and hoping fails, existing and wanting to cease to exist.

Depression is one of the symptoms of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, which often goes undiagnosed and untreated masquerading behind what is seen as a psychological problem. But the problems are often a mixed bag of physical and emotional pain and addressing just the “psychological” side of this does not always lead to long-lasting relief. Inversely, treating just the physical symptoms and focusing solely on the biochemical balance of thyroid hormones risks underestimating the emotional toll that the condition has on the sufferer. Little else is more frustrating than being told that your tests are “normal” because they fit into the “normal range” for lab tests and that therefore there is nothing “wrong” with you. I was faced with this reaction for a number of years, dismissed as a “hypochondriac” and told to “cheer up” or even “eat more salt” when a problem with my thyroid had already been established. Having “subclinical” hypothyroidism does not make the patient’s emotional responses any less real, their effects any less keenly felt on their lives. I wish doctors and in particular general practitioners would be more aware of the close inter-relationship between thyroid and other hormones in the human body. (But this is to be addressed in another post).